As a change agent, promoting a different culture of aging and different ways to support each other as we grow older or grow with dementia, I have struggled with how to do this – how do we promote change? A wise mentor said to me that sometimes the best place to start is with yourself. To share your perspective through your story.

He asked, How did you change?

It is critical that this story is an authentic one, he stressed. In particular, it has to include the mistakes you made, and humility, in assuring each other that we will continue to make more mistakes. And that hopefully, as they become a part of our stories, we learn and grow from our mistakes.

So, let’s settle in for the story of how and why I became a revisionist gerontologist.

Once upon a time I became a gerontologist. This “title” of gerontologist refers to a person who has an advanced degree in gerontology or aging studies. But what made me a revisionist gerontologist was something else. It was a paradigm shift.

Per the definition of revisionist:

A revisionist is “an advocate of revision; a reviser; any advocate of doctrines, theories, or practices that depart from established authority or doctrine.”

As a revisionist gerontologist I believe we need to change the paradigm of aging and dementia.

It is important for us all to realize that paradigm shifts are made, not born. I was not born a revisionist gerontologist. I grew into one.

How were the seeds planted?

I am a proud gerontologist. The academic field of gerontology gave me my title, and an important framework for me to think about growing older or growing with dementia. But the academic framework of gerontology is not the basis of my knowledge about aging and dementia. The basis of my knowledge about aging is from human experience.

Everything I know really grew from elders and people living with dementia who have sat with me and shared their stories.

So, yes, I have a degree in gerontology, but my knowledge is really from many years of having the honor of listening to elders – elders from all sorts of places – about their lives, their concerns, their wisdom, their joys. They are truly what has made me a gerontologist, and a revisionist one at that.

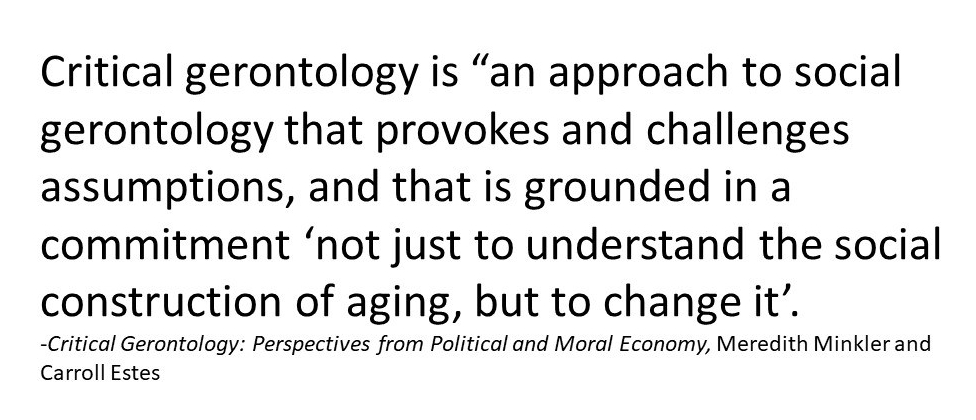

Don’t get me wrong. The academic study has been vital to my development. What it particularly gave me was a lens through which to be continually curious about aging, and to always question what we think we know. This is in the spirit of “critical gerontology”, which is really a thing.

Don’t get me wrong. The academic study has been vital to my development. What it particularly gave me was a lens through which to be continually curious about aging, and to always question what we think we know. This is in the spirit of “critical gerontology”, which is really a thing.

Critical gerontology helped my paradigm shift grow. It helped me see that perhaps there were some cracks in the field of gerontology. And that even within a field that is so well-intentioned, and so new, there is a need for gerontologists to continually be open to newer possibilities, and to create a culture of learning.

Critical gerontology helped my paradigm shift grow. It helped me see that perhaps there were some cracks in the field of gerontology. And that even within a field that is so well-intentioned, and so new, there is a need for gerontologists to continually be open to newer possibilities, and to create a culture of learning.

Really, to listen more. To pay attention.

I needed to listen more, with elders, with people with dementia, and with those who care for both.

So, I listened. I paid attention. I learned and grew from listening, and sometimes, not listening. And I saw some more cracks.

You see, the things I was hearing and seeing in being with elders and people living with dementia were raising questions to me. About how we saw older people and people with dementia, and how this paradigm of aging and dementia was being operationalized into systems that were not created from or with elders and people living with dementia, but for them.

By well-meaning professionals like myself.

I had been working in nursing homes and assisted living communities and I was very unsettled by what I was experiencing. They were so institutional, and there was very little focus on people as individuals.

I found myself blindly doing what everyone else was doing because that was the way it was done. I found myself becoming institutionalized.

I thought I could do better. I thought we could do better. Yet, I felt powerless and overwhelmed with changing “the system”. So, I left long-term care.

I started working with people in their earlier experiences of dementia, what we have traditionally called “early stage”. I facilitated education and support groups for them and their care partners. As I really listened to what people were experiencing, and saw things from their perspective, I realized that, although it had been well-intentioned, I had been approaching people with dementia often from my perspective.

The more I listened to and spoke with people with dementia, learning what it was like to have dementia, including their fears, their struggles, and their hopes, the more I realized how much we really did not SEE people with dementia as whole human beings. We saw them as their dementia.

For years I sat and listened to individuals living with dementia as they shared their world with me. And my world changed.

For years I sat and listened to individuals living with dementia as they shared their world with me. And my world changed.

I remember preparing for a presentation to a group of people living with dementia on the symptoms of dementia, and I realized that the way we had always talked about dementia, to professional and family caregivers, did not include the voices of people living with dementia. When I thought about the language we had used to describe people with dementia – regular, normal people with whom I had been sitting and listening – I realized that I had to find another way to think and talk about this.

I could not talk to a group of people with dementia, describing the seven stages of the global deterioration scale to them, and explain how they are measured as humans on this scale – based only on their weaknesses and judged only by their medical diagnosis. I had listened and learned from their perspectives – that these “stages” denied them being able to think about themselves as individuals, and it caused us to not think of them as individuals.

Sitting with people living with dementia, and learning who they were as human beings, as well as how they were living with dementia – struggling with it, and even living well with it – this was the greatest gift to my career as a gerontologist. It changed everything for me.

These experiences with people living with dementia taught me an important lesson, and a lesson that I had not really learned from my gerontology classes or textbooks. To SEE people.

People living with dementia sharing their lives with me was my gateway to being a revisionist gerontologist.

It opened the gates. I found my tribe in Pioneer Network. I learned about culture change and person-centered care. I saw there were other ways to support each other as we grow older.

I became increasingly aware of needing to change the way we see each other as we grow older and grow with dementia, and that this starts with SEEING people as multidimensional individuals.

Being a revisionary gerontologist does not mean I have the answers. To me, being a revisionary gerontologist is, in many ways, about embracing imperfection, but challenging myself and others to do better for elders and people living with dementia. I am a work in progress. We are a work in progress.

Why am I sharing my story? We all have a story. There is a journey in each of us as we change the culture of how we see each other as we grow older or grow with dementia. Paradigm shifts are made, not born. And they live in our stories. What is your story?

Thank you for sharing your story, Sonya, from a member of your tribe. We’ve known each other a long time but I only knew a part of your story and not how you got to where you are today. Your story illustrates how our life experiences shape our perspectives and how those of us in the aging field from different disciplines (e.g. you’re a gerontologist, Penny and I are social workers, Joan is a nurse) evolve over time and use those experiences to inform our life’s work.

LikeLike

Thanks Cathy! A multi dimensional experience of growing older needs multidimensional people to support it!

LikeLike

Thanks Sonya for sharing your story and reminding me that people ‘grow’ with dementia, just as we all grow older, and perhaps wiser. Because living with dementia is usually seen as ‘losing something’, the concept of ‘growth’ or gaining something with dementia, has helped me to shift my paradigm a bit more.

Elroy Jespersen

LikeLike

Thanks, Elroy! I can’t take credit for this insight- it is what people living with dementia taught me!

LikeLike

Sonya,

As always, you blow me away with your insights! Keep up the good work!

Your friend,

Laura

LikeLiked by 1 person

The love is mutual, friend!

LikeLike